Study Looked at Pathogens Among Afghanistan War Wounded

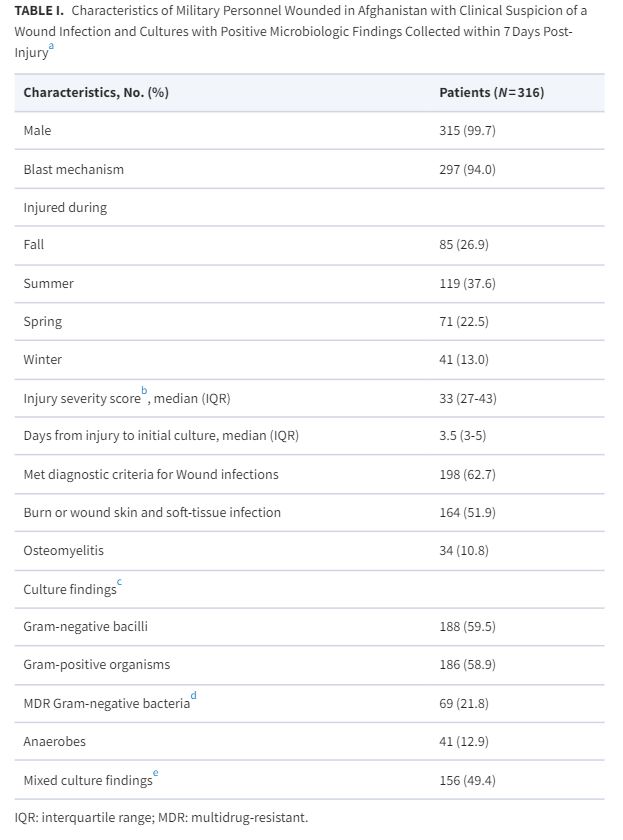

Click to Enlarge: a. Study population is focused on the first week of trauma care following injury, which includes medevac and a 2-3 day stay at Landstuhl Regional Medical Center followed by transition to a U.S. hospital.

b. See Linn (1995)32 for information on injury severity score.

c. Includes both colonizing and infection isolates recovered from wound cultures. Colonizing isolates were from wounds with clinical suspicion, but did not meet diagnostic criteria for infection.

d. Multidrug-resistant bacteria primarily included Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter spp., and Enterobacter spp.

e. Includes a combination of Gram-negative bacilli, Gram-positive organisms, and/or anaerobes. Source: Military Medicine

SAN ANTONIO — Battlefield-related wound infections complicate recovery from combat casualties. A new study described what pathogens are more likely to cause morbidity at what times of the year to help better manage the infections.

“Seasonality of these infections was demonstrated in previous conflicts (e.g., Korea) but has not been described with trauma-related healthcare-associated infections from the war in Afghanistan,” according to the Brooke Army Medical Center-led researchers.

Included in the study published in Military Medicine were military personnel wounded in Afghanistan from 2009-2014, medevac’d to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center and then transitioned to participating military hospitals in the United States. All had clinical suspicion of wound infections and wound cultures collected 7 or fewer days post-injury.1

With analysis limited to the first wound culture from the wounded warriors, infecting isolates were collected from skin and soft-tissue infections, osteomyelitis and burn soft-tissue infections. The researchers analyzed the data by season—winter (Dec. 1-February 28/29) spring, (March 1-May 31) summer (June 1-Aug. 31) and fall (Sept. 1-Nov. 30).

Among the 316 patients, 297 (94.0%) sustained blast injuries with a median injury severity score and days from injury to initial culture of 33 and 3.5, respectively, according to the report, and, while all patients had a clinical suspicion of a wound infection, a diagnosis was confirmed in 198 (63%) of them.

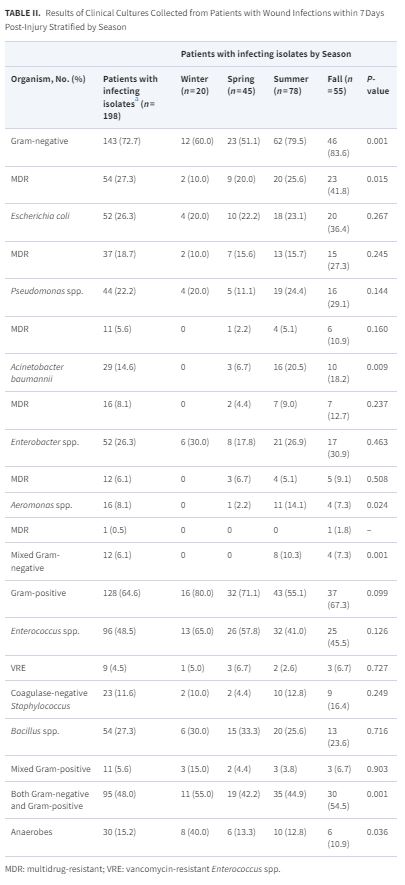

Results indicated that gram-negative bacilli (59.5% of 316) were more commonly isolated from wound cultures in summer (68.1%) and fall (67.1%) vs. winter (43.9%) and spring (45.1%; P < 0.001).

The study team reported that multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacilli (21.8%) were more common in summer (21.8%) and fall (30.6%) vs. winter (7.3%) and spring (19.7%; P = 0.028). “Findings were similar for infecting Gram-negative bacilli (72.7% of 198)-summer (79.5%) and fall (83.6%; P = 0.001)-and infecting MDR Gram-negative bacilli (27.3% of 198)-summer (25.6%) and fall (41.8%; P = 0.015),” the researchers pointed out. “Infecting anaerobes were more common in winter (40%) compared to fall (11%; P = 0.036). Gram-positive organisms were not significantly different by season.”

The study concluded that gram-negative bacilli, including infecting MDR Gram-negative bacilli, were more common in summer/fall months for servicemembers injured in Afghanistan, adding, “this may have implications for empiric antibiotic coverage during these months.”

Click to Enlarge: a. As patients may have more than one isolate recovered, the numbers will sum to more than the total number of patients Source: Military Medicine

Background information in the article advised that infectious disease complications after battlefield wounds historically have been a significant cause of both morbidity and mortality among warfighters. “With improved treatment, mortality rates associated with infected war wounds dropped from 1 in 25 during World War II to 1 in 100 during the Gulf War,” according to the study authors. “The dramatic decline in mortality has been attributed to the evolving standard of battlefield war wound care including rapid administration of antibiotics, prompt surgical intervention, and decreased time from point of injury to definitive care. Those surviving previously fatal injuries frequently undergo prolonged hospitalizations with associated infectious complications.”

Healthcare-Associated Infections

Most of the infections, such as sepsis, pneumonia and bloodstream infections developing a median of 5-7 days post-injury and osteomyelitis occurring 26-28 days post-injury, are determined to be healthcare-associated.

An investigation into a multidrug-resistant (MDR) Acinetobacter baumannii–calcoaceticus complex infections among personnel wounded in Iraq determined that the source of infection was multifactorial, with the primary source being health care-associated transmission of pathogens in field hospitals, the researchers explained.

“Despite great strides in improving the treatment of war wounds, infectious complications remain a significant source of morbidity among service members and contribute to poor wound healing after amputation, as well as serve as a source for recurrent infections, osteomyelitis, and sepsis,” they added, explaining the importance of understanding and being able to predict the microbiology of war wounds and associated infections.

“One aspect in the development of effective empiric antibiotic regimens is the understanding of seasonality and its role in the microbiologic composition of war wounds,” the authors wrote. “Since Alexander Fleming began identifying organisms present in war wounds in the pre-antibiotic era, seasonality of war wound microbiology has been of interest in every major conflict to include the World Wars, Korean, Vietnam, and Gulf War conflicts. Additionally, although the seasonality of colonizing and infecting pathogens has previously been described, this has yet to be discussed in relation to battlefield-related infections. With this in mind, we sought to evaluate the effect that seasonal factors play on the microbiology of wound cultures in service members injured in Afghanistan.”

Noting that combat casualty care has substantially advanced in recent conflicts and that injured personnel are now rapidly transitioned out of theater to LRMC (a 2-3 day stay) followed by transition to tertiary-care centers in the United States for definitive care, the researchers said their data enhance lessons garnered from previous conflicts.

Unlike the predominant Gram-positive infecting isolates seen during the World Wars and in the Korean War, our results show higher rates of Gram-negative infecting isolates in summer months, similar to that seen in the Vietnam War,” they explained. “In addition, because of increasing rates of combat-related extremity injuries occurring secondary to improvised explosive devices, military personnel may be increasingly exposed to pelvic floor injuries, resulting in early enteric Gram-negative colonization and subsequent infections.”

The study noted that, while assessing for seasonal variation of culture findings, potential confounding factors were not examined, including combat fighting seasons with especially high casualty numbers occurring April through September, the limited ability for servicemembers to bathe effectively, proximity to combat support hospitals, prior prophylactic antibiotic therapy and specific type of blast-related injury mechanism.

Still, the study team said its findings “may have implications for empiric antibiotic coverage during these months. In addition, these results show that environmental and climate factors can influence the microbiologic makeup of infecting wounds. Further studies exploring various aspects of environmental and climate impacts on wound microbiology are warranted.”

- Soderstrom MA, Blyth DM, Carson ML, Campbell WR, et. al. Seasonality of Microbiology of Combat-Related Wounds and Wound Infections in Afghanistan. Mil Med. 2023 Nov 8;188(Supplement_6):304-310. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usad115. PMID: 37948254; PMCID: PMC10637295.